1952 Republican National Convention on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1952 Republican National Convention was held at the

The 1952 Republican National Convention was held at the

File:General Dwight D. Eisenhower.jpg,

File:Douglas MacArthur 58-61.jpg,

File:Harold Stassen.jpg,

File:RobertATaft.jpg,

File:Earl Warren Portrait, half figure, seated, facing front, as Governor.jpg,

The contest for the presidential nomination was expected to be a battle between the party's moderate to liberal and conservative wings. Moderate and liberal Republicans (the " Eastern Establishment"), led by New York Governor

The contest for the presidential nomination was expected to be a battle between the party's moderate to liberal and conservative wings. Moderate and liberal Republicans (the " Eastern Establishment"), led by New York Governor

Republican Party platform of 1952

at ''The American Presidency Project''

Eisenhower nomination acceptance speech for President at RNC

(transcript) at ''The American Presidency Project''

Video of Eisenhower nomination acceptance speech for President at RNC from C-SPAN (via YouTube)

Audio of Eisenhower nomination acceptance speech for President at RNC

{{Authority control Republican National Convention Political conventions in Chicago Republican National Conventions Republican National Republican National Convention Republican National Convention

The 1952 Republican National Convention was held at the

The 1952 Republican National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre

The International Amphitheatre was an indoor arena located in Chicago, Illinois, that opened in 1934 and was demolished in 1999. It was located on the west side of Halsted Street, at 42nd Street, on the city's south side, in the Canaryville n ...

in Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

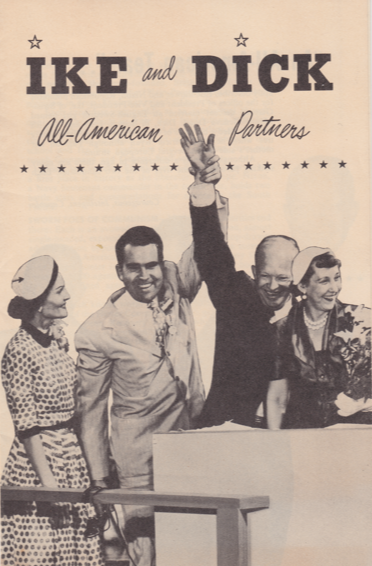

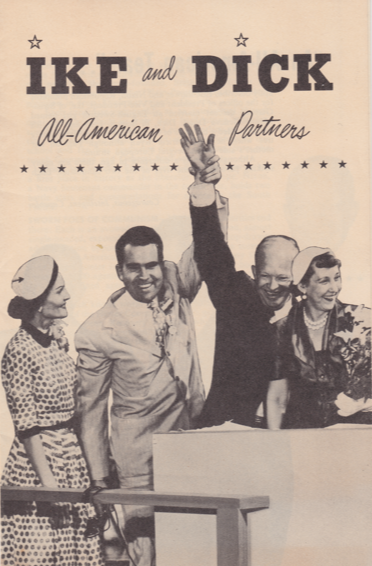

from July 7 to 11, 1952, and nominated the popular general and war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

of New York, nicknamed "Ike," for president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

and the anti-communist crusading Senator from California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, Richard M. Nixon, for vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

.

The Republican platform

Platform may refer to:

Technology

* Computing platform, a framework on which applications may be run

* Platform game, a genre of video games

* Car platform, a set of components shared by several vehicle models

* Weapons platform, a system or ...

pledged to end the unpopular war in Korea, supported the development of nuclear weapons as a deterrence strategy, to fire all "the loafers, incompetents and unnecessary employees" at the State Department, condemned the Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

and Truman administrations' economic policies, supported retention of the Taft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

, opposed " discrimination against race, religion or national origin", supported "Federal action toward the elimination of lynching", and pledged to bring an end to communist subversion in the United States.

Presidential candidates

Withdrew before the convention

* Businessman Riley A. Bender ofIllinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

* Former Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

George T. Mickelson

George Theodore Mickelson (July 23, 1903 – February 28, 1965) was an American lawyer, 16th Attorney General of South Dakota and 18th Governor of South Dakota, and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Distri ...

of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

* Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

Thomas H. Werdel of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

* Senator Wayne Morse

Wayne Lyman Morse (October 20, 1900 – July 22, 1974) was an American attorney and United States Senator from Oregon. Morse is well known for opposing his party's leadership and for his opposition to the Vietnam War on constitutional grounds.

...

of Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

Candidates at the convention

Keynote speech

The keynote speech was delivered by MacArthur, who had become a hero to Republicans after President Truman relieved him of command in 1951 because of their disagreement about how to prosecute theKorean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, and had hopes of obtaining the presidential nomination. In his address, MacArthur condemned the Truman administration for America's perceived loss of status on the international stage, including criticism of the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

and the administration's handling of the war in Korea. MacArthur also criticized Truman on the domestic front, blaming his administration for wages that failed to keep pace with post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

inflation. The speech was not well received, and did nothing to aid MacArthur's presidential campaign. He curtailed his post-convention speeches and remained out of the public eye until after the election.

The balloting

The contest for the presidential nomination was expected to be a battle between the party's moderate to liberal and conservative wings. Moderate and liberal Republicans (the " Eastern Establishment"), led by New York Governor

The contest for the presidential nomination was expected to be a battle between the party's moderate to liberal and conservative wings. Moderate and liberal Republicans (the " Eastern Establishment"), led by New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

, the party's unsuccessful presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948, were largely supporters of Eisenhower or Warren. The conservative wing was led by Taft, who had unsuccessfully tried for the presidential nomination in 1940 and 1948.

In a pre-convention fight over the seating of delegates, Eisenhower supporters charged the Taft campaign with improperly seeking to obtain delegates from Texas, Georgia and Louisiana, states that were part of the Democratic Party's "Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

" where Republicans had little or no organization because they traditionally did not do well in general elections. The Taft-dominated Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is a U.S. Political action committee, political committee that assists the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party of the United States. It is responsible for developing and promoting the Republi ...

supported Taft in the dispute. When delegate committees met to consider the issue before the convention convened, they sustained Eisenhower's position. Stripped of 42 delegates from the disputed states, Taft's backers realized their chances of beating Eisenhower were slim.

In his remarks during the delegate fight, Taft supporter Everett Dirksen

Everett McKinley Dirksen (January 4, 1896 – September 7, 1969) was an American politician. A Republican, he represented Illinois in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. As Senate Minority Leader from 1959 u ...

harshly criticized Dewey and the moderate to liberal wing of the party, which had dominated it since 1940. In describing the party's failed presidential campaigns of 1940, 1944 and 1948, he pointed at Dewey, who was seated with the New York delegation, and shouted "We followed you before and you took us down the road to defeat!" Dirksen's condemnation of Dewey touched off sustained anti-Dewey and pro-Taft demonstrations.

Dirksen nominated Taft. Eisenhower was nominated by Maryland Governor Theodore McKeldin

Theodore Roosevelt McKeldin (November 20, 1900August 10, 1974) was an American politician. He was a member of the Republican Party, served as mayor of Baltimore twice, from 1943 to 1947 and again from 1963 to 1967. McKeldin was the 53rd Governor ...

, who made obvious overtures to the conservative wing by mentioning Eisenhower's Midwestern Kansas roots and the fact that he had begun attendance at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

during the presidential administration of Robert Taft's father, William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. McKeldin described Eisenhower's career at the highest levels of the military as evidence that he was able to assume the responsibilities of the presidency immediately and his international renown as an asset that would enable the party to unify its disparate wings and make inroads among Democratic and independent voters. McKeldin's nomination was seconded by Kansas Governor Edward F. Arn, Oregon Republican Party Chairman Robert A. Elliott, Mrs. Alberta Green, a delegate from West Plains, Missouri

West Plains is a city in, and the county seat of Howell County, Missouri, United States. The population was 12,184 at the 2020 census.

History

The history of West Plains can be traced back to 1832, when settler Josiah Howell (after whom Howell ...

, and Hobson R. Reynolds, a state legislator from Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

.

After the nominations were completed, including speeches on behalf of Earl Warren, Harold Stassen

Harold Edward Stassen (April 13, 1907 – March 4, 2001) was an American politician who was the 25th Governor of Minnesota. He was a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for President of the United States in 1948, considered for a ti ...

, and Douglas MacArthur, the delegates proceeded to vote. After the first ballot, Eisenhower had 595 votes, nine short of the nomination, which required 604. Taft had 500, Warren 81, Stassen 20, and MacArthur 10. Warren's backers refused to change their votes to Eisenhower because they still hoped for a deadlock that might enable Warren to obtain the nomination as a compromise choice. Stassen had not received 10 percent of the vote, which freed his home state Minnesota delegates from their pledge to support him. Most of the Stassen delegates, led by Warren E. Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986. Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul Colleg ...

, changed their votes to Eisenhower, which gave him 614 votes and the presidential nomination. Other delegations then began to switch to Eisenhower, and the revised first ballot total was:

After the revised totals were announced, Taft and Warren supporters moved to unanimously nominate Eisenhower, which the delegates did. As soon as Eisenhower was nominated, he visited Taft personally to request his endorsement and obtain a promise that Taft would support the Republican ticket. Taft immediately agreed, and loyally backed Eisenhower during the general election campaign.

Vice presidential nomination

Senator Richard M. Nixon's speech at a state Republican Party fundraiser inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

on May 8, 1952 impressed Governor Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

, who was an Eisenhower supporter and had formed a pro-Eisenhower delegation from New York to attend the national convention. In a private meeting after the speech, Dewey suggested to Nixon that he would make a suitable vice presidential candidate on the ticket with Eisenhower.

Nixon attended the convention as a delegate pledged to Earl Warren and represented California on the convention's platform committee. In pre-convention remarks to reporters, Nixon touted Warren as the most prominent dark horse and suggested that if Warren was not the presidential nominee, Nixon's Senate colleague William Knowland

William Fife Knowland (June 26, 1908 – February 23, 1974) was an American politician and newspaper publisher. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a United States Senator from California from 1945 to 1959. He was Senate Majority Le ...

would be a good choice for vice president. As the convention proceedings continued, Warren became concerned that Nixon was working for Eisenhower while ostensibly pledged to Warren. Warren asked Paul H. Davis of the Hoover Institution

The Hoover Institution (officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace; abbreviated as Hoover) is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, an ...

at Stanford University, who had been a vice president at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

while Eisenhower was the school's president, to tell Eisenhower that Warren resented such actions and wanted them to stop. Eisenhower informed Davis that he did not oppose Warren, because if Taft and Eisenhower deadlocked, then Warren would be his first choice for the nomination. In the same conversation, Eisenhower indicated that if he won the nomination, Nixon would be his first choice for the vice presidency, because Eisenhower believed the party needed to promote leaders who were aggressive, capable, and young. Eisenhower later developed a list of seven potential candidates, with Nixon's name at the top.

After Eisenhower was nominated, his key supporters met to discuss vice presidential possibilities. Eisenhower informed the group's chairman, Herbert Brownell Jr.

Herbert Brownell Jr. (February 20, 1904 – May 1, 1996) was an American lawyer and Republican politician. From 1953 to 1957, he served as United States Attorney General in the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Early life

Brow ...

that he did not wish to appear to dictate to the convention by formally sponsoring a single candidate, so the group reviewed several, including Taft, Everett Dirksen

Everett McKinley Dirksen (January 4, 1896 – September 7, 1969) was an American politician. A Republican, he represented Illinois in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. As Senate Minority Leader from 1959 u ...

, and Alfred E. Driscoll

Alfred Eastlack Driscoll (October 25, 1902 – March 9, 1975) was an American Republican Party politician, who served in the New Jersey Senate (1939–1941) representing Camden County, who served as the 43rd governor of New Jersey, and as ...

, all of whom they quickly rejected. Dewey then raised Nixon's name; the group quickly concurred. Brownell checked with Eisenhower, who indicated his approval. Brownell then called Nixon to inform him that he was Eisenhower's choice. Nixon accepted, then departed for Eisenhower's hotel room to discuss the details of the campaign and Eisenhower's plans for his vice president if the ticket was successful in the general election.

The delegates soon assembled to formalize the selection. Nixon asked Knowland to nominate him, and Knowland agreed. After Taft supporter John W. Bricker declined Nixon's request to second the nomination, Driscoll agreed to do so. There were no other candidates, and Nixon was nominated by acclamation.

Television coverage

The 1952 Republican convention was the first political convention to be televised live, coast-to-coast. Experiments in regionally broadcasting conventions took place during the Republican and Democratic conventions in 1948; however, 1952 was the first year in which networks carried nationwide coverage of political conventions. Fixed cameras were placed at the back and the sides of the International Amphitheatre for the press to use collectively. None of these offered a straight shot of the podium on stage, so many networks supplemented their coverage with shots from their own portable cameras. The impact of the Republican Convention broadcast was an immediate one. After carefully watching the Republican Convention, the Democratic Party made last-minute alterations to their convention held in the same venue to make their broadcast more appealing to television audiences. They constructed a tower in the center of the convention hall to allow for a better shot of the podium, and Democrats exercised more control over camera shots and the conduct of delegates in front of the cameras. By 1956, the effect of television further affected both the Republican and Democratic conventions. Conventions were compacted in length, with daytime sessions being largely eliminated and the amount of welcoming speeches and parliamentary organization speeches being decreased (such as seconding speeches for vice-presidential candidates, which were eliminated). Additionally, conventions were given overlying campaign themes, and their sessions were scheduled in order to maximize exposure to prime-time audience. To provide a more telegenic broadcast, convention halls were decked out in banners and other decorations, and television cameras were positioned at more flattering angles.See also

* History of the United States Republican Party *List of Republican National Conventions

This is a list of Republican National Conventions. The quadrennial convention is the presidential nominating convention of the Republican Party of the United States.

List of Republican National Conventions

Note: Conventions whose nominees won ...

* 1952 Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 21 to July 26, 1952, which was the same arena the Republicans had gathered in a few weeks earlier for their national convention f ...

* U.S. presidential nominating convention

* U.S. presidential election, 1952

References

Further reading

*External links

Republican Party platform of 1952

at ''The American Presidency Project''

Eisenhower nomination acceptance speech for President at RNC

(transcript) at ''The American Presidency Project''

Video of Eisenhower nomination acceptance speech for President at RNC from C-SPAN (via YouTube)

Audio of Eisenhower nomination acceptance speech for President at RNC

{{Authority control Republican National Convention Political conventions in Chicago Republican National Conventions Republican National Republican National Convention Republican National Convention